Adam “King Ad-Rock” Horovitz and Mike “Mike D” Diamond — two founding members of the legendary Beastie Boys — spend the first hundred or so pages of the new voluminous Beastie Boys Book describing New York City as it appeared in the early 1980s. It’s a bit wild, with lots of (unsupervised) teens hanging out at clubs, causing mischief, and discovering music both before and of their time. It was in that setting that Horovitz and Diamond met Adam “MCA” Yauch, discovered and dabbled in the hardcore punk music scene, and eventually went on to form one of the most popular hip hop groups of all time. And while the Beastie Boys were active for three decades working with multiple DJs, producers, and musicians, if there was ever a permanent fourth member of the band, you might say it was New York City itself.

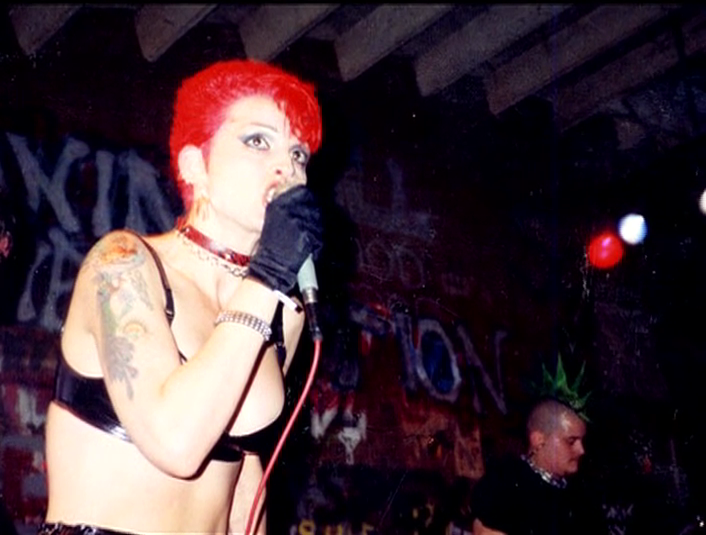

If you (like me) discovered the Beasties in 1987 shortly after MTV added “Fight For Your Right (To Party)” into heavy video rotation, you should be aware that the recording of the band’s debut Licensed to Ill doesn’t begin until shortly after page 200. The book covers a lot of historical ground before ramping up to the band’s mainstream breakthrough hit. The earliest incarnation of the Beastie Boys can be traced back to a hardcore band called The Young Aborigines, featuring Michael Diamond (and, notably, Kate Schellenbach from Luscious Jackson). It was in 1981 when Adam Yauch joined the band that the group adopted the Beastie Boy moniker. Around the time Adam Horovitz joined the group in 1982, the Boys had already begun to dip their toes in the newly emerging rap genre. Not long after, the guys recorded their first rap single (a prank phone call played a drum beat titled “Cooky Puss”). For a short period of time the band split their live sets between hardcore punk songs and feeble raps, but as the band’s infatuation with hip hop culture continued to blossom, Kate Schellenbach was left behind, Rick Rubin (co-founder of Def Jam Records and the band’s first DJ) was in, and the lineup that existed when the band broke big was officially set in place.

The band’s story, almost 600 pages of it, is relayed here by Diamond and Horovitz in a first-person and mostly-linear fashion. The chapters are small and bite-sized — many only two or three pages in length. Like the musical samples the band is famous for, the narrative is sprinkled with guest appearances, recollections, and sidebars. Just like “Bouillabaisse,” a spicy fish-based soup that the Beastie Boys once named a track after, the book contains everything from a comedic review of the band’s attire by fashion journalist Andre Leon Talley, to a series of wisecracks about their music videos by comedian and New York transplant Amy Poehler. With frequent changes in authors and even typography, the book’s style is more Paul’s Boutique than Licensed to Ill.

With so many stories thrown in, it’s interesting to note who and what weren’t included between the covers. DJ Hurricane’s name (the band’s touring DJ for more than a decade) appears exactly twice in the book: once in a short list of the band’s former DJs, and once in the following sentence: “Then DJ Hurricane played some kind of intro, and we went onstage…” Mix Master Mike, Hurricane’s replacement and the band’s permanent DJ since 1998, gets a single two-page article in the form of an odd interplanetary space diary entry. Again, this is a book that devotes twenty pages to the kid who designed the first Beastie Boys website, and gives Spike Jonze another twenty to add captions to a series of photographs taken during the “Sabotage” video shoot. The nearly complete absence of any discussion in regards to the band’s two primary DJs is a glaring hole.

Also missing for the most part, in case you were looking for some, is dirt. There’s no mention of the band’s flare up with Prodigy, or the 2015 lawsuit against Monster Energy Drinks for using their music without permission. Other than briefly touching on their well-publicized beef with 3rd Base’s MC Serch (the Boys once threw garbage from an upstairs window at Serch when he rang their doorbell and interrupted their hangover sleep), the book mostly side steps (or completely ignores) any conflicts the band may have experienced, both external and internal.

The one exception is their falling out with Rick Rubin, parts of which are covered in more detail here than ever before. The Boys, particularly Horovitz, pull no punches when it comes to documenting the parting of ways with the co-owner of their label, DJ, and at least at one time, kindred spirit. Horovitz paints Rubin as a control freak in the studio and a flake who jumped ship during the Beastie Boys tour, leaving them without a DJ. Details about withholding royalty payments from their debut album (which sold more than ten-million copies) are included. While Beastie Boys Book is obviously Horovitz’s and Diamond’s recollection of things, some of their criticism seems one-sided. Many well-established factors in the band’s split with Def Jam (including the fact that Rubin had pegged Horovitz for a solo act, while fellow Def Jam co-founder Russell Simmons was looking the steal Yauch from the group) go unmentioned. Both Rhyming and Stealing: A History of the Beastie Boys by Angus Batey (1998) and The Men Behind Def Jam by Alex Ogg (2002) cite Rolling Stone interviews with the guys about the falling out that don’t appear here.

Other than the split with Def Jam (a beef I assumed had been long been buried, until I read this book), the band seems content to not only let sleeping dogs lie, but make amends where they can. Most of their poor decisions and falling outs are blamed on their own immaturity and alcohol abuse. The take the high road and make several heartfelt apologies within the book, going as far as to give the early-ousted Kate Schellenbach her own mini-chapter to comment on her departure.

The Beastie Boys Book is not the ultimate all-encompassing story of the band; instead, it’s 600 pages worth of memories from a couple of guys (and a few of their friends) recounting one of the most memorable and amazing musical trips through modern history. From requesting an inflatable penis as a stage prop for their first tour to organizing the Tibetan Freedom Concerts in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park (attended by more than 120,000 people), the Beastie Boys have grown a lot, seen a lot, and done a lot, and this book documents hundreds of moments that took place along the way.

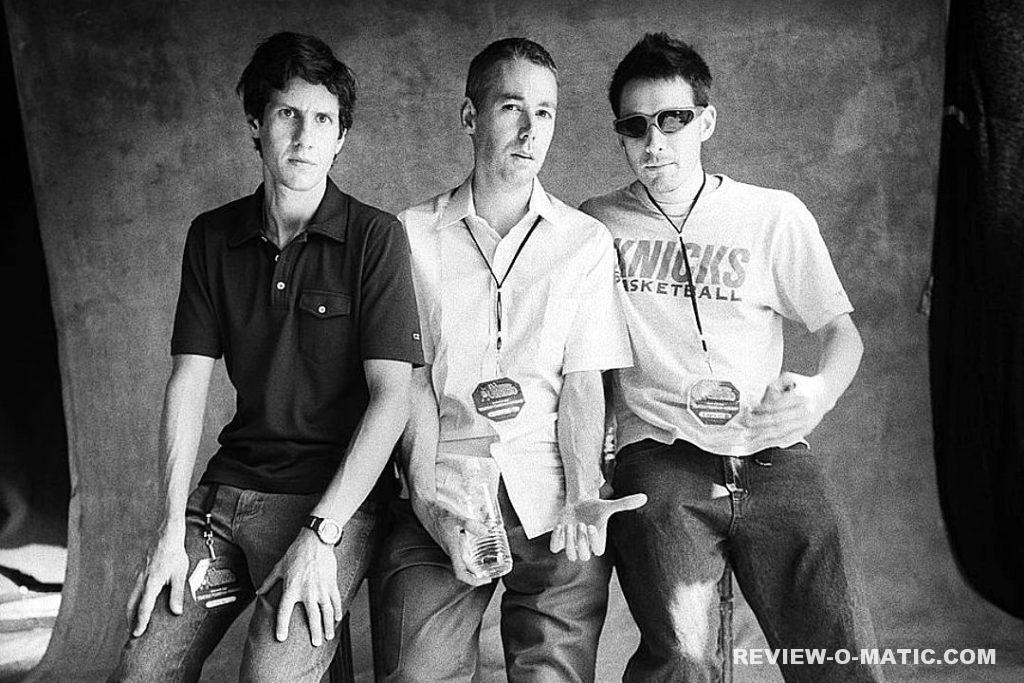

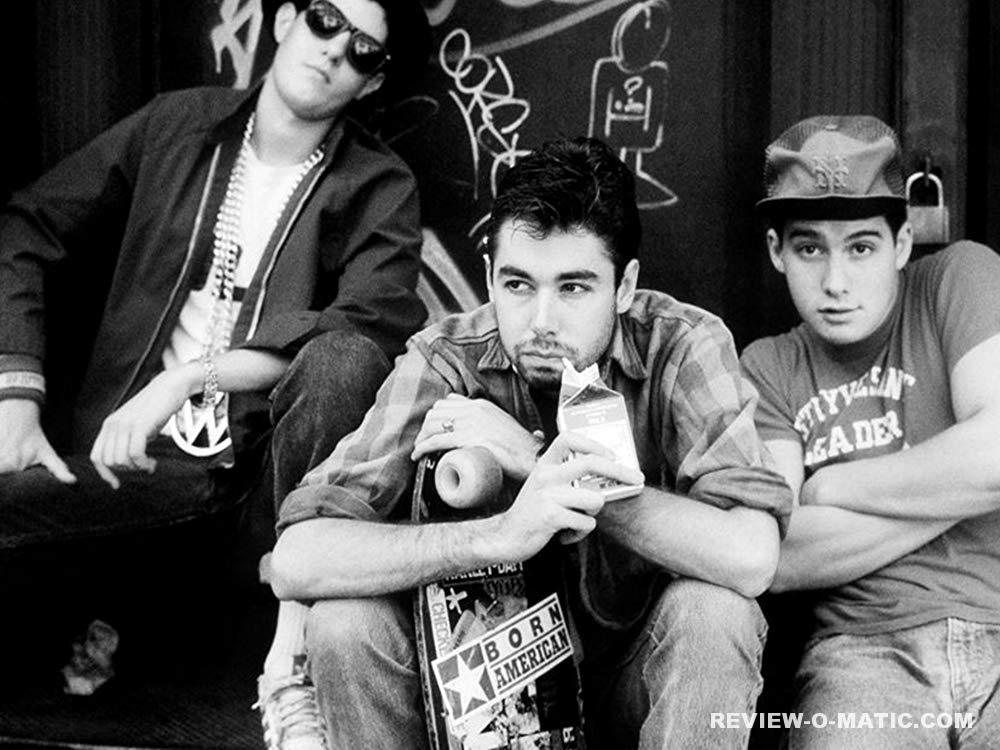

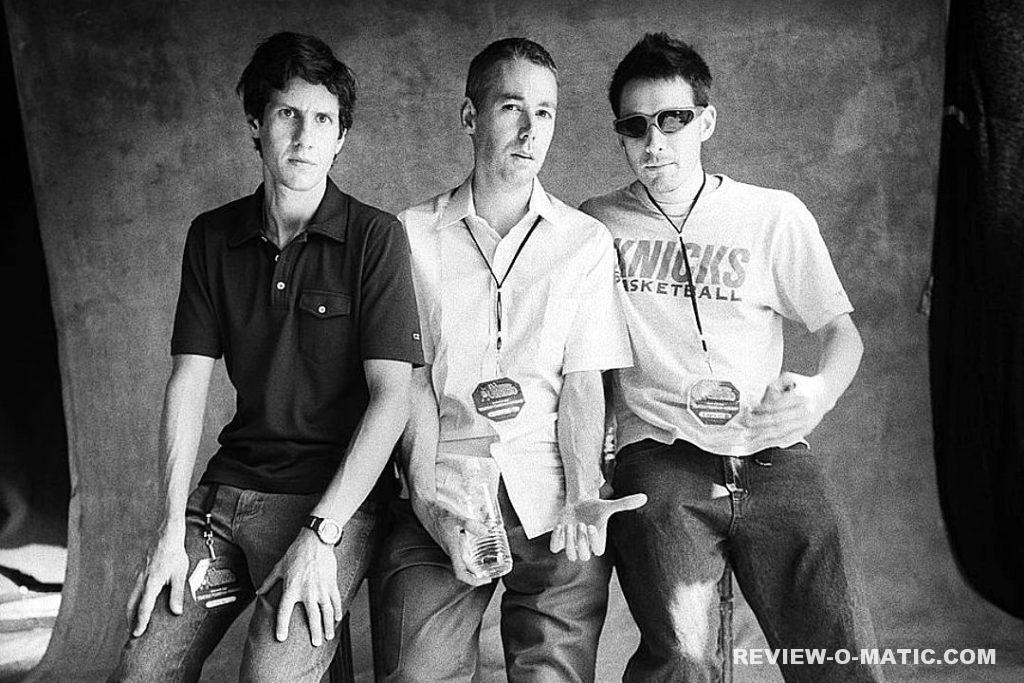

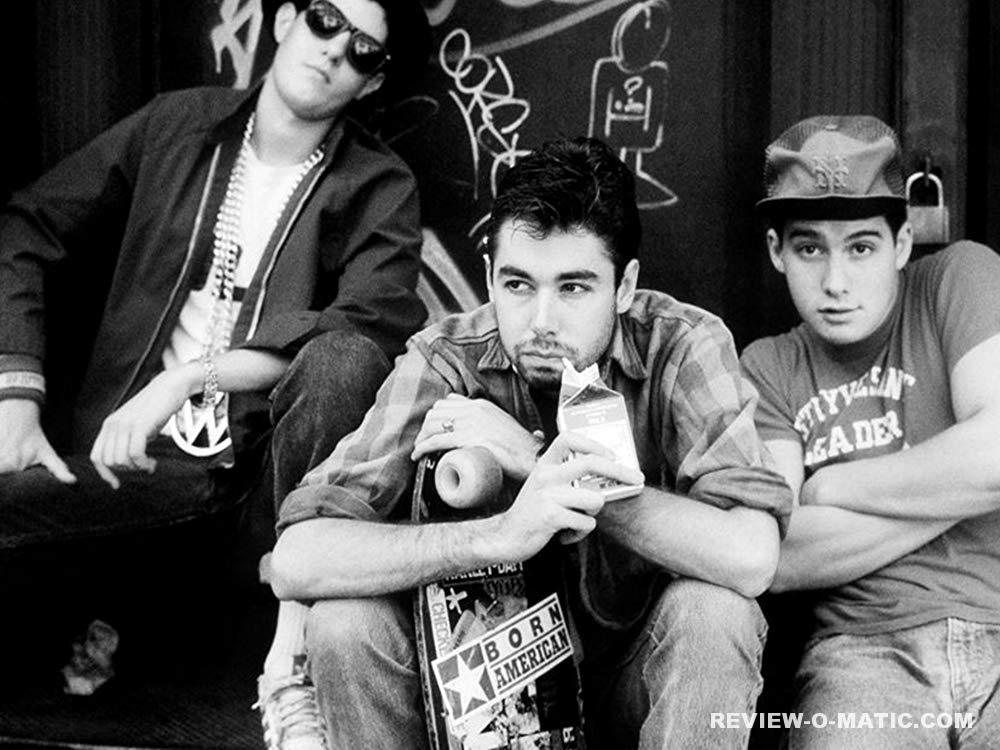

Also included are dozens and dozens of candid photographs culled from the band’s personal collection. Everything from the pre-Beasties (decked out in hardcore gear) all the way to live shots from the band’s final tour are on display here, many in full color. Specific moments, like Mike D tweaking the sliders on a mixing board in the studio as Run-DMC look on, capture pivotal moments in time. In an era where celebrities post every meal on Instagram, it’s easy to forget how rare it was to take (and keep) so many photos in the 1980s, and it’s wonderful to see so many of them here on display.

If the book is missing anything at all, it’s Adam “MCA” Yauch’s unique voice. Yauch was often the glue that held the band together and frequently the guy steering the ship. Yauch passed away from cancer in 2012 at the age of 47, thus bringing an untimely close to the band’s career. Both Horovitz and Diamond have done a good job of both including Yaunch’s stories while being careful not to speak for him, but they readily admit upfront that his unique view of the world would have added a different flavor to the book.

If you’ve always wanted to know more about the real Tadrach and Johnny Ryall, the King Adrock’s thoughts on carrying cassette tapes around New York City (winter is better, because you have more pockets), what it was like to tour with Madonna, and a million other things, Beastie Boys Book is for you. It answers a lot of questions, poses a few new ones, and, sadly, is the closest thing to a new Beastie Boys album we’re likely to ever get.